Discovery and Credential Access via Kerberos & NTLM: A Detection-Focused Approach

Introduction

Windows environments rely heavily on authentication protocols like NTLM and Kerberos. While these protocols serve critical security purposes, they are also commonly abused during malicious activities.

This article explains how to detect suspicious behaviors related to Domain Account Discovery and Credential Access, specifically focusing on Enumeration, Brute Force, and Password Spraying attempts via NTLM and Kerberos.

All detection examples are mapped to techniques from the MITRE ATT&CK framework:

- Discovery → T1087.002: Account Discovery – Domain Account

- Credential Access → T1110.003: Brute Force – Password Spraying

Kerberos vs. NTLM: A Quick Comparison

NTLM (New Technology LAN Manager)

NTLM is a legacy authentication protocol using challenge-response mechanisms. The client sends a username, receives a random challenge, and responds with a hash of the challenge encrypted using the user’s password hash. The server forwards this to the domain controller, which verifies it and grants access if it matches . While still used for backward compatibility, it’s less secure than Kerberos and more vulnerable to brute-force and relay attacks.

Kerberos

Kerberos is the default authentication protocol in Active Directory domains. It uses tickets and symmetric encryption (via Key Distribution Center (KDC)), offering authentication between client and server and proving identity to services. Generally more secure, but is still subject to attacks such as pre‑authentication brute force, password spraying, and Kerberoasting if not correctly configured.

Enabling Auditing and Collecting Relevant Events

In order to detect attacks leveraging NTLM and Kerberos authentication, it’s essential to enable the correct Windows auditing policies and collect logs from the appropriate event channels.

Here you can find the policy recommendations provided by Microsoft’s System Audit Policy.

Required Event Logs

| Protocol | Event ID | Description | Log Source |

|---|---|---|---|

| Kerberos | 4768 | TGT Request | Security → Security channel |

| Kerberos | 4771 | Pre-authentication failed | Security → Security channel |

| NTLM | 4776 | NTLM Authentication attempt | Security → Security channel |

Enable Audit Policies

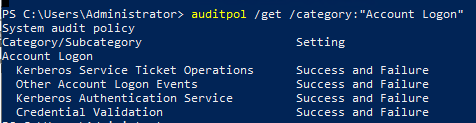

To collect these events, ensure the following Advanced Audit Policies are enabled via Group Policy:

Account Logon

Audit Kerberos Authentication Service(Success, Failure)Audit Kerberos Service Ticket Operations(Success, Failure)Audit Credential Validation(Success, Failure)

You can verify these via PowerShell :

auditpol /get /category:"Account Logon"

Detection Strategy Overview

Detection of these activities is based on detecting Windows Security events 4768, 4771, 4776, then analyzing failed authentication attempts and using aggregation logic over short time windows to highlight suspicious patterns.

Before diving into the detection rules, here’s a quick reference table for the status codes used in the rules, which indicate the type of failure.

The proposed detection queries are written in KQL language (Elastic SIEM).

Status Code Reference Table

| Status Code | Meaning | Category | Protocol |

|---|---|---|---|

0xC0000064 | User not found | Enumeration | NTLM |

0xC000006A | Password incorrect (valid user) | Brute Force | NTLM |

0xC0000234 | Account locked out | Brute Force (post) | NTLM |

0xC000006D | Username or password invalid | Brute Force (generic) | NTLM |

0xC000006E | Account restriction (e.g., logon hours) | Brute Force (valid user blocked) | NTLM |

0x6 | Unknown user (Kerberos TGT request) | Enumeration | Kerberos |

0x18 | Bad password (Kerberos pre-auth failure) | Brute Force / Password Spraying | Kerberos |

Detection Rules for Kerberos

1. Kerberos Enumeration Attempt

event.category:authentication and event.code: 4768

and winlog.event_data.Status: 0x6

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by source.ip ≥ 1 when unique user.name ≥ 10

[ within 5 minutes ]

Event ID 4768 refers to a TGT (Ticket Granting Ticket) request. A status of 0x6 means “unknown username”, which can indicate username enumeration. If a single IP attempts multiple distinct usernames in a short window, it likely reflects an enumeration scan.

2. Kerberos Brute Force Attempt

event.category:authentication and event.code: 4771

and winlog.event_data.Status: 0x18

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by user.name, source.ip ≥ 20

[ within 5 minutes ]

Event ID 4771 represents pre-authentication failure. Status 0x18 means “bad password”. Repeated failed logins for the same username from one source IP is typical brute force behavior.

3. Kerberos Password Spraying Attempt

event.category:authentication and event.code: 4771

and winlog.event_data.Status: 0x18

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by source.ip ≥ 1 when unique user.name ≥ 10

[ within 5 minutes ]

Same event and status as above, but this time the pattern involves many usernames and fewer attempts per user – which aligns with password spraying. Excluding machine accounts (*$) helps reduce noise.

Detection Rules for NTLM

4. NTLM Enumeration Attempt

event.code: 4776

and winlog.event_data.Status: "0xc0000064"

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by winlog.event_data.Workstation ≥ 1 when unique user.name ≥ 10

[ within 5 minutes ]

Event ID 4776 corresponds to NTLM logon attempts. Status 0xc0000064 = “user name does not exist”. Multiple failed attempts across usernames indicate a possible enumeration.

5. NTLM Brute Force Attempt

event.code: 4776

and winlog.event_data.Status: ("0xc000006a" or "0xC0000234" or "0xc000006d" or "0xc000006e")

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by winlog.event_data.Workstation, user.name ≥ 20

[ within 5 minutes ]

These status codes represent invalid credentials, locked accounts, or disabled users. Repeated login attempts per user from the same host are consistent with brute force behavior.

6. NTLM Password Spraying Attempt

event.code: 4776

and winlog.event_data.Status: ("0xc000006a" or "0xC0000234" or "0xc000006d" or "0xc000006e")

and NOT user.name: *$

Aggregated by winlog.event_data.Workstation ≥ 1 when unique user.name ≥ 10

[ within 5 minutes ]

Just like in Kerberos spraying, attackers try a single password across many usernames. This rule looks for multiple failed attempts across many users within a short time frame.

Final Thoughts

By correlating failed authentication attempts, usernames, IP addresses, and status codes, we can effectively detect enumeration, brute force, and spraying attacks over both NTLM and Kerberos.

Key points:

- Monitor Event IDs 4768, 4771, and 4776

- Use status codes to classify attack type

- Exclude service accounts and anonymized logons

- Implement aggregation logic to reduce false positives

These detection rules are a starting point. Always adapt thresholds and filters based on the size and behavior of your environment and, if possible, enrich the events with threat intelligence sources.

References

https://www.crowdstrike.com/en-us/cybersecurity-101/identity-protection/windows-ntlm

https://www.ultimatewindowssecurity.com/securitylog/encyclopedia/

https://www.elastic.co/docs/reference/integrations/system#security

https://docs.extrahop.com/9.3/walkthrough-bundle-active-directory

These Solutions are Engineered by Humans

Did you learn from this article? Perhaps you’re already familiar with some of the techniques above? If you find cybersecurity issues interesting, maybe you could start in a cybersecurity or similar position here at Würth Phoenix.